Sections of the Cemetery

Soldiers' Cemetery

Why are Confederate soldiers buried here?

In the fall of 1863, Chattanooga, Tennessee, was evacuated ahead of the advancing Union Army. Hospitals serving the Confederate Army of Tennessee under the direction of Dr. Samuel H. Stout were relocated to several Georgia towns in the region. There were five hospitals established in LaGrange: Cannon, Law, Oliver, St. Mary’s, and Receiving & Distribution—names they came with from Chattanooga. While we don’t know their exact locations, contemporary accounts note several churches and buildings downtown were turned into hospitals, as well as Smith Hall at LaGrange

Female College, now LaGrange College. It is likely the hospitals were moved again in late 1864.

In addition to soldiers, several orderlies were buried at the south end of the cemetery. They were enslaved people who worked in the hospitals. Several names of those who died appear in hospital records, but their graves were not marked. Wooden fencing originally built around the cemetery excluded these graves.

Most of the stone grave markers seen here were added in 1913. Originally, there were wooden markers. By 1877, they were deteriorating, and the Ladies Memorial Association made a list of the names. The United Daughters of the Confederacy later raised funds to replace them with stone markers.

Unknown Graves

More than 1,000 people were buried here in previously unmarked graves. Today we recognize and honor their presence.

Some of the first African Americans buried here were enslaved orderlies from Civil War hospitals. After the war, other African Americans—including those newly freed from enslavement—began using the plot for burials. Unfortunately, very few were recorded or permanently marked.

The City of LaGrange acknowledged this as a cemetery for Black people as early as March 3, 1875. In City Council meeting minutes, the street superintendent reported his department had, “Set out two Sweet Gums, Five Poplars, and two white mulberries in colored cemetery also cleaned out the same.”

It is speculated that some of those buried here came from a pauper farm adjacent to the cemetery. The county purchased the farm in 1870, and it operated until about 1900 when the property was acquired for a cotton mill. Troup County was economically depressed after the war. Many citizens, particularly newly freed people of color, became destitute with no means of work or support. A poor person could be deemed an “inmate” of the pauper farm by the courts. Residents grew crops and raised livestock for their own use as the farm was intended to be self-sufficient. Any surplus went to inmates in the county jail or was sold.

Horace King

Horace King, a skilled builder and engineer, overcame the obstacles of slavery to become a renowned bridge builder and entrepreneur in the 19th-century American South. He learned to read, write, and build at a young age, eventually forming a rare partnership with his owner, contractor John Godwin. King’s skills eventually surpassed Godwin’s, and he was able to purchase his freedom in 1846, becoming a respected businessman. After the Civil War, he rebuilt many structures, was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives, and passed his construction knowledge on to his children. King’s legacy as a brilliant engineer and influential figure is still evident in the architecture of LaGrange, Georgia, where he is buried.

Wehadkee Creek Bridge

The covered bridge at Mulberry Street Cemetery was placed here in 2022. It was built by Horace King’s son, George King, in 1890 over Wehadkee Creek in an area that is now part of West Point Lake.

This bridge replaced a bridge built by Horace King in 1873 that was swept away by a flood in 1886. The construction is the same Town Lattice Truss method used by the Kings for most of their bridges. This section of bridge is only 60 feet long, but it was more than 110 feet when it spanned Wehadkee Creek. In the 1960s, the bridge was decommissioned and moved to Callaway Gardens in Pine Mountain, Georgia. It was a feature of the Gardens but did not serve a practical function. Today, it links Mulberry Street Cemetery to The Thread, a multi-use trail over Cary Branch. The roof and some of the siding was replaced as part of reinstallation. However, most of the wooden structure is original—a testament to the quality and durability of the construction.

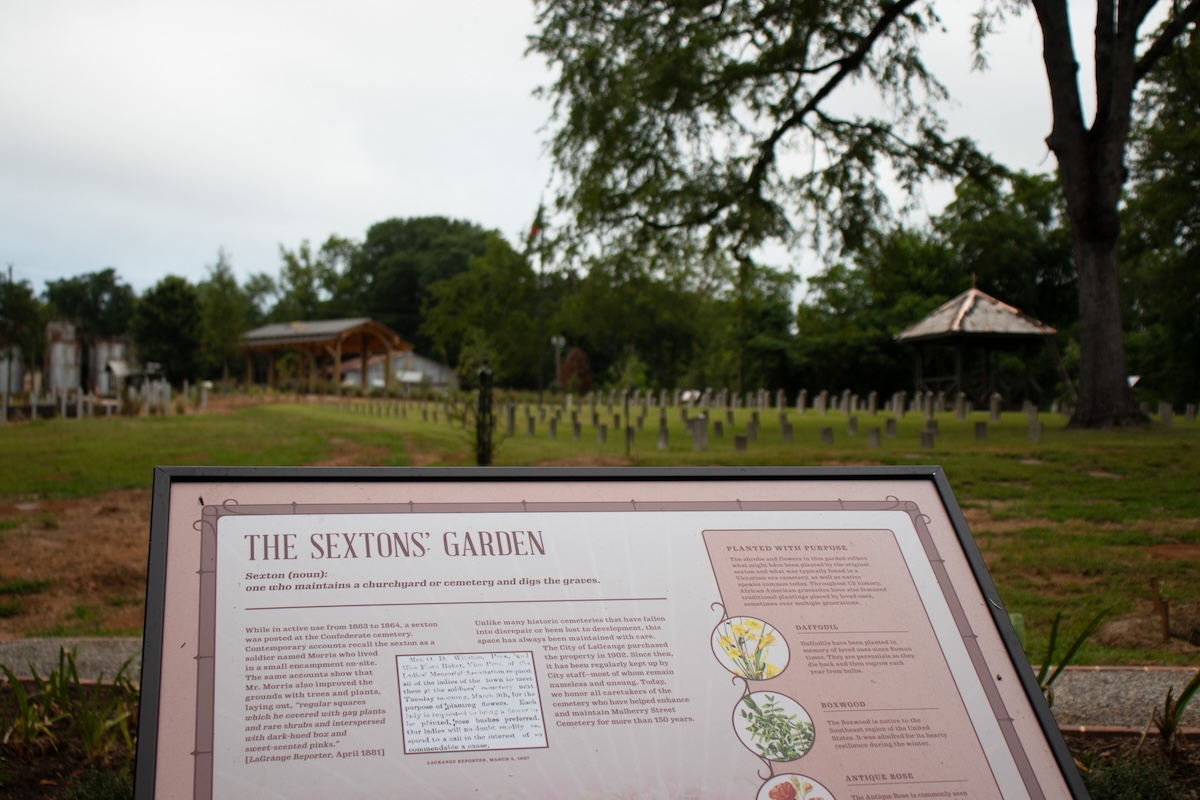

The Sextons' Garden

While in active use from 1863 to 1864, a sexton was posted at the Confederate cemetery. Contemporary accounts recall the sexton as a soldier named Morris who lived in a small encampment on-site. The same accounts show that Mr. Morris also improved the grounds with trees and plants, laying out, “regular squares which he covered with gay plants and rare shrubs and interspersed with dark-hued box and

sweet-scented pinks.” [LaGrange Reporter, April 1881]

Unlike many historic cemeteries that have fallen into disrepair or been lost to development, this space has always been maintained with care. The City of LaGrange purchased the property in 1902. Since then, it has been regularly kept up by City staff—most of whom remain nameless and unsung. Today, we honor all caretakers of the cemetery who have helped enhance and maintain Mulberry Street Cemetery for more than 150 years.

Do You Know Someone Who Is Buried Here?

WE NEED YOUR HELP

Hundreds of unmarked gravesites line the grassy hillside of Mulberry Street Cemetery. Thanks to ground penetrating radar, we know the locations of these sites; however, we do not know the identification of these individuals. Please contact Troup County Archives if you have information about individuals who may be buried here.